What are geisha (geiko in Kyoto and geigi in Kanto and other regions) and maiko?

Geisha are refined entertainment artists, skilled in traditional Japanese arts (dance, singing, musical instruments, games, wit, etc.), and maiko are their “apprentices.”

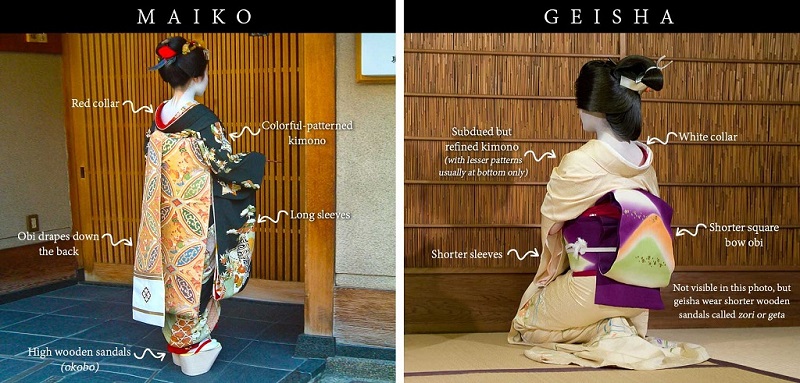

Geisha and maiko wear traditional clothing (the famous kimono 着物) and have elaborate traditional hairstyles.

Geisha literally means “one who practices an art” and maiko “one who dances.”

Both geisha and maiko wear exquisitely beautiful silk kimono, but the elegance of a geisha lies in her gestures and posture (it is said that a geisha can enchant with the simple movement of her hand). Therefore, her clothing and hairstyles are sober, refined, and discreet. A geisha is a fully accomplished artist.

Maiko, on the other hand, are young girls in the prime of their youth, colorful butterflies on the threshold between adolescence and maturity. Their attire is flashy and dazzling, with kimono that reflect the changing seasons, long sleeves, and even longer obi. They wear tall and slightly unstable footwear, which gives their steps a distinctive, almost dancing allure—said to be irresistible to men. Their hairstyles are ornate and full of colorful accessories (kanzashi), which sway and jingle as they move their heads.

These women embody ideals of beauty, stylistic perfection, and traditional feminine elegance; they are iconic and unattainable figures, timeless.

Their role is to provide elegant and refined—yet never boring—entertainment to a wealthy clientele during business meetings or private receptions in teahouses or traditional restaurants.

Gaining access to an encounter with a true geisha is very difficult; without a Japanese “sponsor” to introduce you to that world and open the doors of a teahouse, it is nearly impossible. A good alternative is to attend one of the traditional festivals still held in Kyoto every year (Miyako Odori, Kyō Odori, and Kitano Odori in April, Kamogawa Odori in May, and Gion Odori in November).

In recent times, one can also rely on certain agencies, though it is important to choose carefully.

But is a geisha a prostitute?

Contrary to what many still believe, geisha and maiko have nothing to do with prostitution or the sex industry in general.

The assumption “geisha = prostitute” arose mainly after World War II, when American soldiers stationed in Japan spent time with young women of questionable morals dressed in kimono, who introduced themselves in broken English as “geisha girls” to offer their services for money.

Another reason is the high cost of a geisha’s services (we are talking about four-figure sums for just a few hours). However, many do not realize that the fees these artists receive cover numerous living expenses and repay the investment that their okiya (置屋, the “house” they belong to, as we will discuss later) made in their education, artistic training, and apprenticeship. Not to mention the extremely high cost of their clothing, which, until they start earning, is provided by the okiya itself.

Surely you wouldn’t expect a geisha or a maiko to always wear the same outfit, would you? So be prepared to spend thousands upon thousands of euros for a fine silk kimono.

Today, a geisha’s fee is calculated by the hour, whereas in the past—before clocks—it was measured by the number of incense sticks burned during the evening.

By the way, for those who don’t know, in Tokyo maiko are called Hangyoku 半玉, “half-jewel,” partly because they are not yet full-fledged geisha and because they earn half as much.

In any case, a geisha is not bound to celibacy, and in the past, it sometimes happened that a geisha granted her favors (freely or under pressure from the okiya) to particularly wealthy and/or influential clients—mentors called danna (旦那, literally “husband-client”) with whom they maintained ongoing, more or less platonic relationships. These men could provide constant financial support or help them repay their debts to the okiya in order to gain independence or retire.

Even today, geisha, while maintaining a very private social profile, may have relationships and often, at the end of their careers, they marry.

But let’s delve a little deeper into history

It was in the 17th century that the geisha began to be recognized as figures dedicated to entertainment, initially alongside and later replacing the Oiran (花魁, courtesans in the true sense of the word, what today we would call “high-class prostitutes”). An interesting fact, which not everyone knows, is that the first “geisha” were actually men, who entertained the Oiran’s clients while they waited—rather like movie trailers before the main film.

At the same time, a form of chaste musical entertainment (dances, songs, music) developed in the private homes of samurai and the emerging wealthy merchant class of Edo (ancient Tokyo), where the performers—called odoriko (“dancing girls”)—were young girls trained in the arts from a very early age.

Soon the boundaries began to blur. The fortune of the Oiran (extremely expensive, inaccessible, and tied to a strictly noble world with outdated mannerisms in a rapidly changing society) started to decline, while the little girls who had danced for the samurai grew up and sought their own place in the world and a bowl of rice on the table. Many, to survive, first became prostitutes, but within a few years these women supplanted their male counterparts, becoming the keepers of the traditional entertainment arts we know today. Even the name they adopted, geisha, was a direct reference to the art of entertainment previously performed by men, as if to draw a clear line between entertainment of the body and entertainment of the soul.

Legislation evolved to reflect this change: geisha were confined to the so-called Hanamachi (花街, “flower towns”), the pleasure districts where prostitution was prohibited (after all, you wouldn’t want to take away work from the Oiran). These correspond to today’s “geisha districts,” such as Gion and Pontocho in Kyoto, and Shinbashi and Kagurazaka in Tokyo, among others.

By the early 19th century, the role and figure of the geisha were already consolidated, and there were hanamachi in every city. For example, both Tokyo and Kyoto each had six (in Tokyo: Shinbashi, Yoshicho, Hachioji, Mukojima, Kagurazaka, and Asakusa; in Kyoto: Gion Kobu, Pontocho, Kamishichiken, Miyagawacho, Gion Higashi, and Shimabara).

In the 1920s there were about 80,000 geisha/maiko in Japan, whereas today there are about a thousand, the vast majority concentrated in Kyoto and, to a lesser extent, in Tokyo.

How did one become a geisha?

In the old days (let’s say until the 1930s–1940s), it wasn’t as if a young girl simply decided on her own to become a maiko and then a geisha/geiko. Despite the frills and fine clothing, it was still a very hard profession, entered only after a tough apprenticeship.

Those who endured could become members of the karyūkai (花柳界, “the world of flowers and willows”), as the secret world of the geisha is still called today.

An okiya, which can be translated as “geisha house,” was an entirely female enclave with a strict matriarchal hierarchy. A stern and uncompromising okāsan (お母さん, “mother”) was the undisputed head, and below her the structure descended through geisha, maiko, apprentices, and maids. If the mistress of the house was the okāsan, the geisha of the house ranked second in hierarchy and were respectfully called onēsan (お姉さん, “older sisters”).

In the absence of a biological heir, or if one proved unworthy, the okāsan would appoint one of her geisha as her successor, and upon her death this woman would take over the reins of the “family” and the okiya.

So how did one become a geisha? Well, families—often very poor—would give up their little girls (sometimes as young as six years old, or even younger!) to the okāsan in exchange for money. The girls thus became the property of the okiya, where they received food and lodging in return for their work as maids, while also repaying the okāsan for the money spent to acquire them.

Not very poetic, but not so different from what also happened in our countries with other trades.

Around the age of ten, or in early adolescence, girls who showed potential were enrolled in a special school, the kaburenjō (歌舞練所), where they learned the arts required to become a geisha (dance, singing, playing the shamisen). Of course, they also had to continue working as maids, and the cost of schooling was added to their debt (now you see why a wealthy “sponsor” was necessary).

In this first phase of apprenticeship, which could last years, the girls were not yet called maiko but shikomi-san (仕込みさん).

When this stage ended, the young apprentice became a kind of probationary maiko called minarai (見習い, literally “one who learns by watching,” but also meaning “not enough”). The okāsan would entrust the girl to an experienced geisha, of whom she became both assistant and pupil. Dressed up, the apprentice accompanied her “older sister” to appointments, where she silently observed. She did not receive pay and was not allowed to entertain the guests—her task was only to watch and absorb through osmosis the things that cannot be taught in school but only through experience: how to conduct witty conversation, how to capture a guest’s attention, and so on.

This stage lasted at least a month, depending on the girl’s talents. When the okāsan deemed her ready, the new maiko made her debut with a ceremony called misedashi (見世出し, literally “showing oneself to the world”).

If you think the hardest part was over at that point, you are very mistaken.

A girl could remain a maiko for up to five years before “graduating” and becoming a true geisha. During this period, all her earnings went to the okiya, and resignation was not an option, since she had to repay the house for the costs of her education and clothing.

Life as a maiko was very tough. Beyond total dependence on the okāsan and onēsan, there were even physical restrictions: their hair was styled only once a week, and to avoid ruining such an expensive and elaborate job they had to sleep on a wooden support that kept their heads elevated. The okāsan would often scatter rice around the stand to check if the girls had moved during the night. Many maiko ended up with damaged hair or even bald patches due to the mechanical stress of these hairstyles.

Of course, personal freedom and leisure time were nonexistent.

Once they reached 20 or 21 years of age, the maiko was finally declared a geisha/geiko with a ceremony called erikae (襟替え, literally “turning the collar,” since the collar of a maiko’s kimono is red, while that of a geisha is white).

From that moment on, the woman remained a geisha until she retired or got married.

And today?

Today, the path to becoming a geisha is a little less exhausting, but in essence it remains the same (absolute obedience, strict rules, schooling, and training…).

Child protection and child labor laws, as well as compulsory education until the end of junior high school, mean that it is rare for a girl to start her training before late adolescence, and today very few leave school before the age of 18. Some even decide to become geisha after university.

This means that the apprenticeship process, which once could last up to 10 years, is now compressed into a maximum of 3–5 years.

If a girl chooses this career, she applies to an okiya to be admitted as an apprentice (not an easy step, as one usually needs to be introduced by someone known to the okāsan). The okāsan then speaks with the family, so everyone is aware of what this career involves. If everyone agrees, the girl is accepted into the okiya. Of course, she is no longer “purchased” by the family, but she still has to repay the okiya for everything the okāsan spends on her.

In Kyoto, foreign girls or those considered too mature are not accepted into apprenticeship; the chosen ones must adapt to a lifestyle with old-fashioned rhythms, strict rules, and an inflexible hierarchy. The rules are essentially the same as 100 years ago: contact with the family of origin is minimal and controlled, and the girls are not allowed to have a mobile phone.

In Tokyo and other regions, things are less rigid: older girls are accepted and – very rarely – some foreigners. As far as I know, there are about 7 foreign geisha in total, though not all are active.

If a girl is particularly agée, she becomes a geisha without first being a formal maiko, since she is considered too “old.” However, she must still undergo at least a year of rigorous apprenticeship.

It goes without saying that, because of these “concessions” to modernity and worldliness, in Kyoto they turn up their noses and do not consider a Tokyo geisha to be on the same level as a Geiko.

The tradition of the “sponsor,” the danna, has disappeared.

What does a geisha do after retirement?

Today, there are no particular restrictions on “post-geisha” life, aside from the limits of the education received: someone who has only studied dance and shamisen will hardly become an aerospace engineer.

Most women get married; others open businesses (teahouses, restaurants…), while some work in tourism.

It is also worth remembering that there is no fixed retirement age: although rare, there are still very elderly geisha active today, because for a geisha beauty is not linked to physical attractiveness but to her artistic skills and elegance.

The one I saw, is she really a geisha/maiko? In other words… how can I tell a real geisha from a fake one?

One could write an entire book on this topic.

First of all, we need to learn how to distinguish a geisha from a maiko and to understand the distinctive features of their clothing. As you can see from the photos below, geisha and maiko differ greatly in makeup, hairstyle, clothing, and more…

As a general rule, keep in mind that clothing and makeup become more sober and “mature” as one progresses from junior maiko (beginners) to senior maiko and finally to geisha.

Historically, maiko began their apprenticeship as children, and this is naturally reflected in their traditional clothing, hairstyle, and makeup.

(Photo left by: Joe Baz / CC | center and right by: Annie Guilloret / CC – taken from https://iamaileen.com/understand-japanese-geisha-geiko-maiko-define/)

(Photo left by: Laura Tomàs Avellana / right by: Joi Ito / CC – taken from https://iamaileen.com/understand-japanese-geisha-geiko-maiko-define/)

Let’s start with the maiko

Junior Maiko (first year of apprenticeship):

- Her face is covered with a striking white base (in the past, teahouses were poorly lit, and this made the face stand out better in the candlelight), leaving only a thin line of natural skin around the hairline.

- The white makeup is not applied only to the face, but also to the back of the neck, except for a small area at the nape, left bare in two elongated “V” shapes (three on special occasions such as New Year’s). These uncovered areas are called ashi (“legs”), and they make the neck appear much longer while also adding a subtle touch of seduction.

- The cheeks and the eye area are highlighted with shades of red.

- The eyes are outlined in bright red (known as Kyoto-red). Eyeliner is either not used at all or applied only very lightly (unless it is a special occasion).

- The eyebrows are redrawn and accented in red.

- The lips are not completely covered with lipstick; the red is applied only to the lower lip.

- The hair is styled in a very elaborate way, usually in the Wareshinobu (割れしのぶ) style.

https://geimei.tumblr.com/hairstyles

This hairstyle is usually not worn after the age of 18.

-

The hair is full of ornaments to highlight the wealth of the okiya and to draw attention to the youth of the maiko.

The fan-shaped ornament on the right (left in the photo…) is called bira bira kanzashi (bira bira is an onomatopoeia, evoking the tinkling sound and the play of light on the ornament). On special occasions, two are used.

The floral “ball” on the left (right in the photo…) is called Tsumami kanzashi, and all the flowers are handmade from silk. It takes on different names depending on its design. The hanging part visible in the photo on the right is called bura-bura (another onomatopoeia), and it is used only during the first year of service as a maiko.

The kanzashi and their colors follow the rhythm of the seasons.

Naturally, there are special hairstyles and makeup for major occasions. -

As for the kimono, the style is furisode (a formal dress for unmarried girls), with very long sleeves. It emphasizes the fact that maiko are still young girls on the threshold between childhood and adulthood. The kimono, strictly made of silk and weighing between 10 and 20 kg (!!!), has a very long hem, which the maiko holds up with her left hand as she walks. The patterns on the kimono vary and reflect the changing seasons. The decorations cover almost the entire kimono, starting from the shoulders.

An interesting fact is that maiko kimonos have folds/pleats at the shoulders: given the very young age of apprentices in the past, their height and body shape would change over the years, so the kimono had to be adjustable to their physical growth.

For dancing, a special kimono with a train is worn, called hikizuri.

-

The collar is red, decorated with light embroidery.

-

The obi (belt) is called darari no obi; it is extremely long (over 5 meters!) and at the bottom it is embroidered with the crest/mark of the maiko’s okiya. The mark has a double function. The first is simple: a connoisseur can immediately recognize the house the maiko belongs to. The second goes back several centuries, when these girls (10–12 years old) stayed in teahouses until late at night; at some point they would collapse from exhaustion and fall asleep, but thanks to the symbol, the teahouse staff knew where to return them.

-

A special mention for the obiage, the sash used to tie and secure the obi, visible in the photo below. Maiko always wear a red obiage, which must stand out clearly from the obi.

- Finally, let’s mention the comfortable shoes, the famous wooden clogs called Okobo, which (if they don’t twist an ankle on the first outing) give maiko their famous swaying walk.

Senior Maiko (from the second year until the last year of apprenticeship or just before debuting as a geisha):

-

The white base on the face and neck does not change.

-

The cheeks and eye area are highlighted with a much lighter shade of red than before (closer to the pink of cherry blossoms than to red).

-

The eyes are outlined in black and deep red.

-

The eyebrows are redrawn and accented in red.

-

The lips are still only partially covered, but red is applied to both lips.

-

The hair is still styled in a very elaborate way:

-

in the Wareshinobu (割れしのぶ) style if the maiko is under 18 (see photo above)

-

in the Ofuku (おふく) style, a bit more “sober,” if the maiko is over 18 and/or approaching the end of her apprenticeship.

-

-

-

in the Sakkō (先笄) style, worn during the last two weeks before officially becoming a geisha. This is an extremely elaborate hairstyle, traditionally reserved for newlyweds, and it symbolizes the rite of passage from maiko to geisha, which takes place during the erikae ceremony. The hair is intricately braided, with a single lock left free, which the okāsan and the other maiko and geisha of the okiya cut during the ceremony.

-

-

Even senior maiko have special hairstyles and makeup for major occasions.

-

On some of these occasions, maiko blacken their teeth, which in the past was considered a sign of beauty and very sexy.

-

As for hair ornaments, the hanging bura-bura disappears.

-

Kimono decorations become more “sober,” and only one shoulder of the kimono is decorated.

-

The obiage is still red, but if the apprenticeship is coming to an end and the rank change is approaching, the obiage starts to be tucked into the obi and made less visible.

-

The collar gradually tends more toward white and is finely embroidered in red.

-

Maiko approaching their debut as geisha are no longer forced to wear okobo, but can wear the more comfortable geta or zori for longer walks.

Let’s move on to the geisha

-

In general, a geisha’s makeup is less pronounced and more “measured” compared to that of a maiko. A geisha is an adult woman who does not need to flaunt her perfection.

-

The eyeliner becomes more defined, but the red shades are reduced:

-

The application of red on the lips is broader.

-

The “V” shapes on the neck are smaller and less visible.

-

Since the postwar period, geisha have been allowed to wear wigs, instead of enduring the same tortures as a maiko for hairstyling. These are custom-made wigs, crafted with real hair and very expensive. They are regularly maintained by a specialized hairdresser, either at scheduled intervals or whenever needed. The typical hairstyle for a geisha’s wig is a high, formal chignon called Taka Shimada (高島田). The hair frames the face and features a pronounced widow’s peak at the front. Each geisha has more than one wig with different hairstyles, more or less formal, to wear on special occasions.

Fun facts:

-

A geisha wearing a silver “bow” under the chignon is still tied to an okiya and has not yet paid off her debt.

-

Maiko close to “graduation” may also wear their hair in a Shimada-style chignon, but never in the Taka Shimada style.

-

For certain special occasions, geisha do not use wigs and instead style their own natural hair.

-

The geisha wears a “kosode,” a special version of the “tomesode” kimono, the most formal style for married women. The sleeves are much shorter than those of a maiko, and the shoulders are smooth, without pleats. The patterns and decorations of the kimono start from the lower hem and extend up to the waist, but no higher. For dancing, geisha also wear a hikizuri kimono, though it is less ornate and showy than that of a maiko.

-

The collar is strictly white, usually without any ornamental motifs or embroidery.

-

The obi (belt) is much less bulky and more compact than that of a maiko (and half the length). It is called “taiko musubi obi” because its shape resembles that of traditional taiko drums.

-

The obiage can be white, light-colored, or red, but it is always strictly tucked into the obi and only barely visible.

-

On their feet, they wear geta and zori.

So how can I recognize a real geisha/maiko from an impersonator or a tourist in disguise?

Making use of what I explained above and remembering a few simple but foolproof tricks:

-

If she is wearing a wig… she is not a maiko;

-

If she has a cellphone in her hand… she is not a maiko;

-

If she has a short kimono and/or the hem tucked into the obi… she is not a maiko;

-

If they walk around in pairs, smiling as if they were waiting just for you… they are not maiko;

-

Look at the feet! Even if the clogs are the right ones, check how she walks…

-

A tourist “in disguise” will never reach the perfection of a real maiko. There will always be some inconsistency (colors, makeup, accessories) that stands out.

But above all…

-

If she stops to take pictures with you, smiling… she is not a maiko;

-

If you meet her outside a Hanamachi, before 5 p.m., perfectly dressed… she is not a maiko;

Obviously, the same applies to a geisha, even though you rarely see “geisha makeovers.” It’s more common to see groups of girls dressed as maiko accompanied by an older lady dressed in geisha style. Do I really need to tell you not to even think they’re real?

Conclusion

A single web page is certainly not enough to cover such a complex and fascinating subject, but at least it can provide you with some basic knowledge and help you understand what you are seeing.

Always remember that maiko and geisha are professionals doing their job, not sideshow attractions to be chased and photographed like animals in a zoo.

https://www.insidekyoto.com/kyoto-geisha

https://theculturetrip.com/asia/japan/articles/inside-the-secret-world-of-kyotos-oldest-geisha-district/

https://www.toki.tokyo/blogt/2016/8/2/the-history-of-geisha-in-japanese-culture

https://www.toki.tokyo/blogt/2016/6/22/the-life-of-a-geisha

https://en.wikipedia.org/

https://iamaileen.com/understand-japanese-geisha-geiko-maiko-define/

http://www1.odn.ne.jp/maya/english/kanzashi.htm

https://theculturetrip.com/asia/japan/articles/maiko-inside-the-life-of-an-apprentice-geisha/

https://geimei.tumblr.com/hairstyles

https://geimei.tumblr.com/differencesmaikoandgeiko

https://mai-ko.com/maiko-blog/geisha/the-hairstyles-of-geisha-and-maiko/

https://missmyloko.tumblr.com/Anatomy

http://www.maiko-kyoto.jp/fashion/index.html

https://geisha-kai.tumblr.com/

Author

Erika Passerini